Perfume notes are ingredients that make up a fragrance. They are categorized as top notes (citrus, lavendar) heart notes (cinnamon, jasmine) and base notes (vanilla, musk).

This carefully selected blend of ingredients forms the perfume accord, the basic character of a fragrance. Perfume makers carefully select notes to make sure a fragrance both smells pleasant and evokes a certain experience. Notes are classified in a fragrance pyramid.

A perfume’s notes can be separated into three basic categories: top notes, heart notes, and base notes. Notes at the top of the pyramid have a higher volatility (they evaporate faster), while notes at the bottom are longer-lasting.

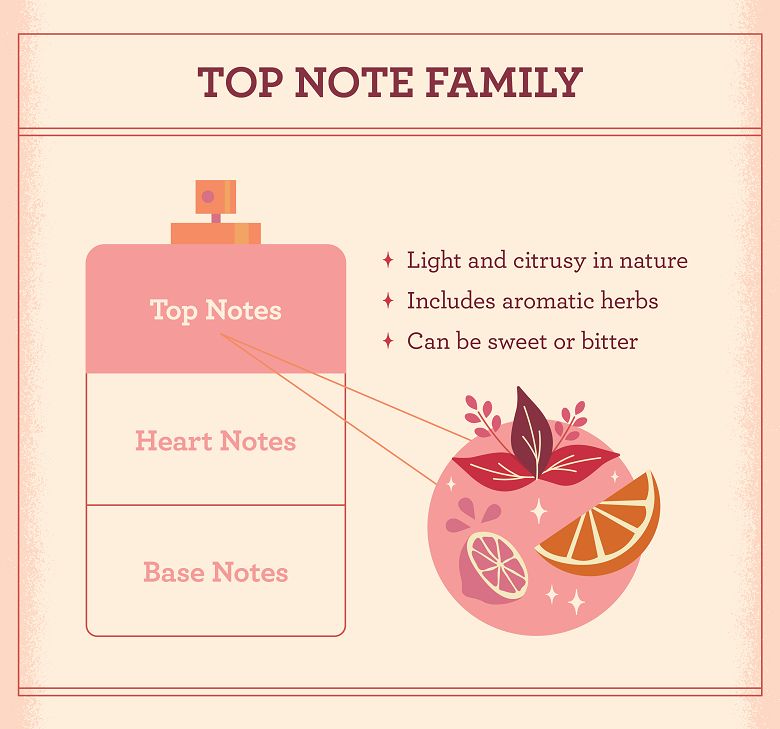

What Are Top Notes?

Top notes, sometimes referred to as headnotes, form the top layer of a fragrance. In other words, top notes are the scents you detect first after spraying a perfume. These play a role in setting first impressions and shaping a fragrance’s story.

Top notes usually evaporate quickly, lingering around for only the first five to fifteen minutes. Their main purpose is to give off an initial scent and then transition smoothly into the next part of the fragrance. As a result, top notes generally consist of lighter and smaller molecules.

Some common top notes include citrus scents – like lemon, orange, and bergamot – as well as light floral notes like lavender and rose. Basil and anise are also commonly used as top notes.

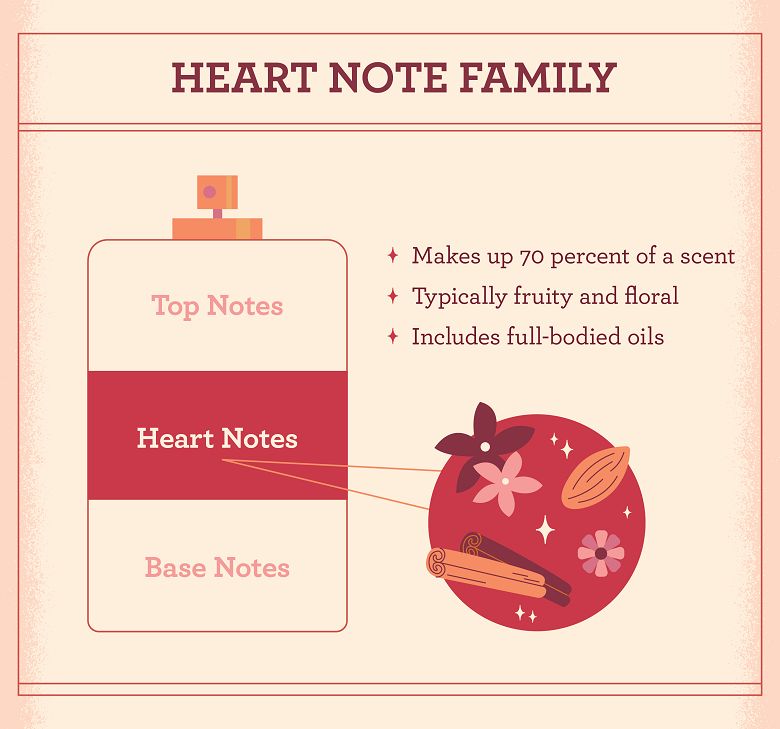

What are Heart Notes?

As the name suggests, heart notes make up the “heart” of the fragrance. Their function is to retain some of the top notes’ aroma while also introducing new scents to deepen the experience. Sometimes referred to as middle notes, the heart notes also serve as a buffer for the base notes, which may not smell as pleasant on their own.

Because they make up around 70 percent of the total scent, heart notes usually last longer than top notes. Heart notes appear as the top notes start to fade and remain evident for the full life of the fragrance.

Heart notes include full-bodied, aromatic floral oils like jasmine, geranium, neroli and ylang-ylang, as well as cinnamon, pepper, pine, lemongrass, black pepper and cardamom.

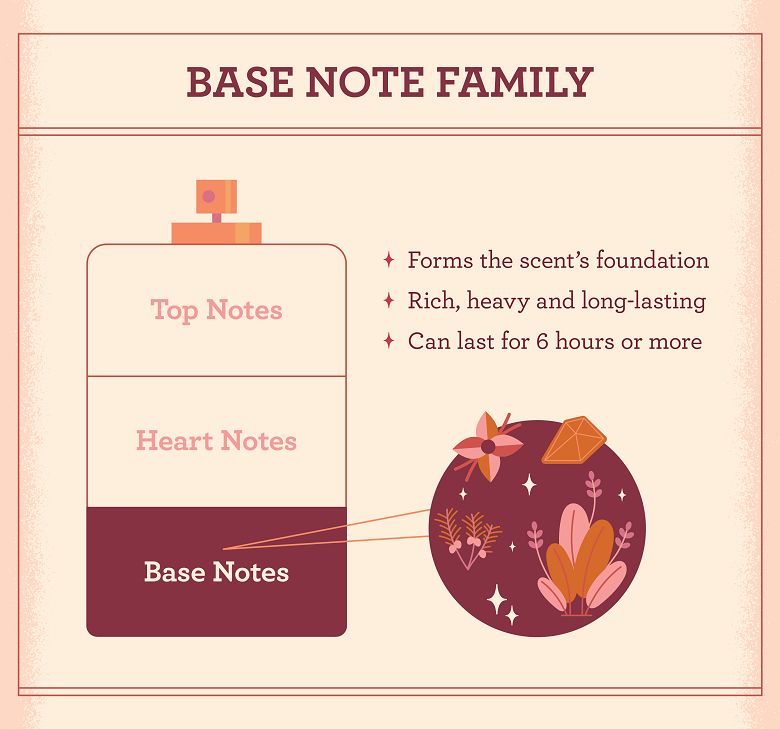

Base Notes

Along with middle notes, base notes form the foundation of the fragrance. They help boost the lighter notes while adding more depth and resonance.

Since they form the perfume’s foundation, base notes are very rich, heavy and long-lasting. They kick in after about 30 minutes and work together with the middle notes to create the fragrance’s scent. Since base notes sink into your skin, their scent lingers the longest and can last for six hours or more.

Popular base notes include vanilla, amber, musk, patchouli, moss and woody notes like sandalwood and cedarwood.

How Do You Identify Perfume Notes?

You can identify perfume notes based on the time passed after the application of the perfume. Top notes are those you smell immediately after the perfume first touches your skin. Once this initial burst fades, the heart notes kick in to form the essence of the perfume. Base notes are the scent that lasts the longest and is the one you remember most.

Every note adds a certain quality to the fragrance. Some of the most common fragrance note categories include fresh, floral, spice, fruits, woods, and musk, each which are typically used in specific note categories. For instance, fresh and floral scents are almost always top notes while woody and musky scents typically appear toward the bottom of the note pyramid.

Here we’ve listed the different types of perfume notes along with an explanation of how they’re used.

Most often by citrus in perfumery we describe the whole spectrum of hesperidic fruits (Hesperidia), named after the Hesperides, nymphs from Greek mythology. These are fruits or citrus-smelling raw materials (notably verbena and lemongrass) and a few are among the most ancient ingredients in perfumery alongside resins. The more modern variations, such as pomelo, grapefruit, yuzu and hassaku, are relatively recent developments in the area of perfume extraction.

The citrus essences are expressed or cold-expressed in most cases to preserve their inherent freshness. Petitgrain is an exception, as it comes from the steam distillation of the twigs and leaves of the bitter orange tree.

Citruses provide a refreshing and effarvescent quality to fragrances, accounting for the top note which tickles our noses with pleasure. They’re helpful for clearing one’s mind and feel sunny and optimistic, lending an air of easy elegance and cleanness. Bergamot especially is an integral part of the classic Eau de Cologne formula. Citruses are a classic companion to more tenacious floral and resinous notes in oriental fragrances and they also provide a good companion to other fruity notes, cutting the sugar and injecting tartness.

Fruity notes beyond citrus (which form a class of its own) have become so popular in recent years that they deserve a category of their own. Vegetable notes are more unusual, sometimes rendered through illusion: an example would be the turnip note that iris rhizome sometimes produces.

As a rule fruits and vegetables are resistant to distillation and extraction processes due to the very high percentage of water in their natural make-up, and they remain a reconstructed note in fragrances. Their effect ranges from the refreshing to the succulent, all the way to the musty and mysterious.

Fruits and vegetables provide a nuanced texture and a refreshing feel in fragrances. Fruits especially have been extremely popular in the floral fruity category in the 2000s, while peach and plum have been major components in classical perfumers’ “bases” (such as the famous Persicol) which produced many of the iconic fragrances of the first half of the 20th century.

Nuts in perfumes usually include the very popular almond (sometimes confused with the cherry-pie tree, which is a heliotrope and most often replicated through the same materials used for heliotrope and mimosa reconstructions), peanuts (as in Bois Farine), hazelnuts (as in Praline de Santal and Mechant Loup). They are all recreated notes. Nutty notes can be beautiful anchors to more ethereal or earthy materials, such as vetiver, as evidenced in Vetiver Tonka in the Herm essences.

A self-evident category of fragrance notes, directly smelling of fragrant blossoms, often rich in nuance: from the banana top note of ylang-ylang, the wine nuances in fresh roses and the powdery, almond-like character of heliotrope, to the camphorous side of freshly-picked tuberose, all the way through the apricot scent of osmanthus, the lemony touches of magnolia and the caramelic facets of lavender, flowers can present surprising sides which never cease to fascinate not just insects, but humans as well.

Many of the flowers are rendered through natural sources: Rose and jasmine are notoriously prized for their incomparable essences, rendered through many different techniques (solvent extraction, enfleurage, distillates). The other natural flower extracts include broom, tuberose, lavender, osmanthus, immortelle, ylang ylang and marigold.

Other flowers refuse to yield their core aroma, or the yield is so minute that replicating the scent in the lab is the way to go. Violet, lotus and water lily do produce an absolute, but it’s very expensive and the yield is so small that only niche and artisanal/all-natural brands can afford to use them.

The following flowers are typically reconstructed in the lab via several synthetic molecules: freesia, peony, lily of the valley, mimosa, heliotrope, violet (most of the time), jonquil, narcissus, hyacinth…

Floral scents add a romantic and often feminine touch to a composition, augmenting the feel of natural beauty derived from smelling a composition, fanning the fleeting top notes onto a tapestry where everything has its place and alleviating some of the heaviness of more tenacious materials, such as resins and balsams. Natural flower extracts also work with the psyche, if we are to believe aromatherapy, in ameliorating the contact with the natural world and providing spiritual uplift.

Flowers play an important role in the floral fragrance family, obviously, but they manage to enter almost all perfume compositions in one form or another, from the lightest eau de cologne to the most lush oriental, even in some masculine colognes. They notably play an intriguing part in “floral orientals” (florientals), where they shine clearest amidst the opulence of materials of Eastern origin.

This is a subgroup within the Flowers group, but it merits its own entry due to the fact that “white flowers” are the basis for a whole fragrance sub-category: the “white florals.” By white flowers, we refer to orange blossom, jasmine, gardenia, tuberose, frangipani. Even though honeysuckle can actually be yellow-colored in nature, its scent profile is not that of yellow flowers (such as mimosa, and it’s typified by the sweet, nectarous headiness of white flowers.

Lily of the valley, although white in color, is classified as a “green floral” as it lacks some of the characteristics of the other white florals and shares facets with other members of the “green floral” groups (according to Edmond Roudnitska’s classification): hyacinth and narcissus.

White flowers have the most narcotic scent of all flowers; lush, opulent and truly intoxicating, almost a code for intense femininity in any fragrance they star in.

By the term “green” we refer to notes of snapped leaves and freshly-cut grasses, which exude a piquant quality. In this classification we find some of the classic pungent essences, such as galbanum, which is actually a resin from a tall type of grass with a bracing, piercingly bitter green odor profile. This is the decidedly spring-like top note of vintage Vent Vert by Balmain where it was first put to use in a starring role.

Fig leaf is a unique note rendered through synthetics which gives the modern “fig” fragrances their bitter-green-allied-to-coconut-sweet scent. Another peculiar leaf note that has a special character is tomato leaf, featured in Eau de Campagne by Sisley, Folavril by A.Goutal and Liberte Acidulee by Les Belles de Nina Ricci.

Violet leaf is a modern green “leaves” note which is very popular. It gives an aqueous feel reminiscent of freshly-cut cucumber to many compositions, especially masculine ones. A subcategory apart are tea leaves notes which infuse blends with their unique aromatic profile, according to which variety the perfumer picks (green, red, white, black, Oolong, etc).

Herbs are refered to as “aromatic notes” by perfumers. These include herbs which we know from cooking, such as rosemary, thyme, mint, tarragon, marjoram, fennel, basil (which is considered a spicy note thanks to its eugenol content), sage, anise. Others, such as artemisia, calamus, angelica and spikenard (jatamansi) have an intensely herbaceous quality that is so distinctive as to immediately characterize the compositions in which they enter.

Fern is the anglification of the fragrance term fougère (fern in French), which is not exactly derived from nature (ferns have minimal scent themselves) but from an historical “accord” between lavender-oakmoss-coumarin which was devised to produce the mysterious note of a green, damp forest. The archetype of this type of fragrance is Fougère Royale by Houbigant, created by Paul Parquet in 1882. The effect was an interplay between sweet and bitter with a woody, damp and cool character, establishing fougères as the quintessential masculine fragrances.

Ferny fragrances recreate the earthy, damp and dark scents of a forest and largely rely on fantasy notes, even though extraction with volatile solvents of the Aspidium fern is possible, though hardly satisfactory in quantity. The subcategory of aromatic fougères, adding spices and herbal notes to the classic structure, is perhaps the most populated masculine colognes category thanks to its pliability.

The Spices group is a familiar category of perfume notes, thanks mainly to their long-standing inclusion in food. Some of them have pride of place in any self-respecting kitchen spice cabinet, such as cinnamon, pepper, cloves, coriander, ginger. Others are more unusual, from the precious hand-picked saffron, to tamarind and caraway and the very gentle, rose-hued pink pepper. True spices are always dried, but there are some herbs which have a spicy tang to them, such as oregano. These can be used both fresh or dry.

Spices are classified as “hot/short” (intense and burning for a short duration) such as cinnamon, and “cold/long” (gentler, giving a cooling sensation rather than burning, with a prolonged aftertaste) such as coriander, caraway and cardamom. This helps the perfumer give the desired effect when handling spices according to his or her concept of a fragrance. They can be coupled with similar materials to reinforce their message, or they can provide a juxtaposing element.

This succulent group of scent notes has really established itself and multiplied henceforth with the advent of “gourmand” fragrances, a sub-division of the Oriental fragrance group, in the 1990s and 2000s. These fragrances, largely built on vanilla, are reminiscent of foody smells, specifically sweets and desserts; ranging from the simpler chocolate, fresh cream and caramel smells to complex or more exotic recipes such as macaroons, crème brulée, the ever popular cupcakes and chewy nougat.

The first successful “gourmand” fragrance was Angel, launching in 1992, which produced a caramel and chocolate effect through the use of ethyl maltol (the scent of cotton candy/sugar caramel), natural patchouli (which has a cocoa facet) alongside industry standard ethyl vanillin. From then on, given Angel’s commercial success, dessert smells flourished and this group of notes is among the most important in contemporary perfumery. Although some natural materials do present facets that are sweet or foody, the vast majority of these notes are reproduced via clever intermingling of naturals and synthetics.

Although mostly used in feminine fragrances, which can more easily encompass sweeter notes, gourmand notes are not excluded from masculine or shared scents.

These edible notes produce a feeling of euphoria and playfulness, resulting in a tingling of the taste buds in addition to the nostrils, thus confirming the fact that flavor is a combination of taste and smell. They make us see our perfume in a completely novel way and are intriguing when used by a skilled perfumer who can manipulate them to create increasingly complex aromas.

Woody notes are dependable and pliable, a sort of a Jack in the deck of a skilled perfumer, providing the bottom of a composition and reinforcing the other elements according to their olfactory profile. Precious few of the woody notes can serve as a top note or middle note, namely rosewood.

The scent profile of woods ranges wildly across the different trees. Some of them can be tarry and phenolic smelling, like guiacwood. Others are austere and reminiscent of a case of new pencils; think cedarwood. Others still are creamy, milky, nuzzling and deeply soft, like sandalwood. And there are those woody notes which are so individual that they can characterise the whole composition: Agarwood/Oud, rather the byproduct of the Aquillaria tree’s fighting of a fungus disease, is so rich and complex that it encompasses nutty, woody, musty, even camphoraceous scents. Or think how pine or fir reminds us of specific seasons, thanks to their associations.

Thought some woody notes are produced via natural means, such as maceration and distillation of the actual wood chips, several other notes, as well as some of the ones that could be produced via the natural product, are produced via lab synthesis. The reasons include sustainability, cost efficiency and safety.

Vetiver and patchouli are interesting exceptions in the group of woody notes, in that vetiver is actually a grass with an intricate root system and patchouli is the leaf of an Eastern bush, but their scent profile is woody, hence the classification. Woody notes are par excellence the domain of masculine fragrances, thanks mostly to the robust association the trees bring to mind and less due to their scent, but their pliability makes them an essential component in feminine and shared fragrances are well. Indeed there are very few fragrances not boasting at least one woody note in their make-up.

Mosses comprise a sub-group, as they consist of parasitical lichen organisms growing on trees, such as oakmoss (Evernia prunastri) and tree moss (Evernia furfuracea). The scent profile of mosses is irreplaceable, though major efforts are made in the fragrance industry to produce scent-identical molecules now that these raw materials have fallen under rationing from the International Fragrance Association (IFRA).

Mosses are inky-bitter in scent, with a deep, disturbing murkiness, darkly green, replicating the forest floor during autumn. For this reason they’re notoriously used as the backbone of the chypre and fougère fragrance families; indeed, oakmoss is one foot of the triad of the accords which comprise the skeleton of these two categories. Their properties are grounding, pensive, introspective and darkly sensual, giving retro fragrances a distinctive quality.

The raw materials falling under the umbrella of resins and balsams are among the most ancient components of perfumes, often the basis of the Oriental family of scents. They are classified into different olfactory profiles according to their aromatic properties.

Soft balsamic-smelling ingredients include vanilla, benzoin, Peru balsam, Tolu balsam (close to Peru but a little sweeter and fresher). They have a gentle tone, while at the same time they’re softly enveloping and have a pronounced character. They fix flowers into lasting longer, and thanks to their properties when used in large quantities, they produce the semi-Orientals or the florientals (in conjunction with rich floral essences).

Resinous balsamic ingredients include opoponax, frankincense/olibanum, myrrh, birch tar, elemi and styrax. These materials are deeper, with a lingering trail which adds originality and projection to a composition. Since they themselves come from the bark of trees in the form of crystalised resin “tears,” they pair very well with woody scents.

The term “animalic” refers to both raw aroma materials and “fantasy” notes (derived from synthesis in the lab) which directly evoke a scent reminiscent of animals—either real ones, or more metaphorically, the libidinous nature of our own human animal instincts—and their primal force.

In perfumery, animal notes were traditionally rendered through deer musk, castoreum, ambergris and civet cats, but nowadays, ethical concerns for these animals’ welfare have rendered their use obsolete and the substitution with synthetic variants a rule. (Only ambergris is by its nature cruelty-free, being naturally expelled by the sperm whale itself in the ocean, but it’s a very rare and expensive ingredient for most commercial use, so synthetics replicating its aroma are the standard practice).

Musk especially has been synthesized in the lab in hundreds of variants, resulting in slightly different odor profiles for each (Galaxolide, Habanolide, Ethyl Brassylate, Allyl Amyl Glycolate etc).

Amber notes are different from ambergris in that the former is a mix of resins producing a warm, sweetish and very deep scent (most often in the “Oriental” family), while the latter is a rather salty, subtly skin-like deep note with no great sweetness to it.

A few cases of animals indirectly used for animalic notes—with absolutely no harm rendered to the animal in question—are hyrax (the petrified excrement of which is used), goat hair tincture, roasted sea shells and beeswax from beehives. Some plants, such as Angelica and Ambrette Seeds, also produce animalic-smelling compounds that replicate musk.

Last but not least, perfumery makes use of “fantasy notes,” rendered through creative mixing of various ingredients or single synthetic reconstitution, that recall the ambience of some scents with animal inferences, such as milk, caviar, starfish, skunk cabbage, bacon, bbq cuts, leather or suede hide.

Fragrances often recreate the scent of popular beverages in some part of their formula, from the festive fizz of Champagne and the caramelized toasty flavor of Coca Cola, to the tropical delights of Pina Colada or the creaminess of a good cup of cappuccino. These recreations are made possible by:

* utilization of ingredients that make up part of the recipe for a given drink (Coca Cola, for instance, in which lime juice, vanilla extract, cinnamon, neroli, orange, coriander and nutmeg feature prominently)

* the association of some raw materials with scents we know from beverages (i.e. the wine-like note in some rose essences, or the gin-like scent of juniper berries, because the latter are actually used to aromatize the former, etc.)

* synthetic molecules which have been engineered to produce the desired effect.

Beverage notes in fragrances provide a succulent, appetizing effect, often combined in fruity floral blends or “gourmand” fragrances which seduce the taste buds as well as the nostrils.

NATURAL AND SYNTHETIC, POPULAR AND WEIRD

In this group we place descriptive notes such as powdery, earthy, and some unusual smells which could be found in perfume compositions.

Share It